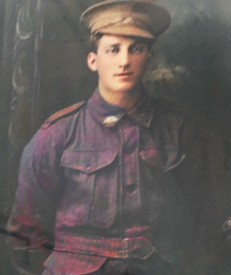

Percival Victor Leopold Short, known as Leo, was a North Melbournian man from a working-class and complicated family. He chose to enlist in the Australian Imperial Forces (AIF) in WWI and WWII. Leo’s WWI experience started in January of 1917 – arriving at his ultimate destination, France, in December of that year. Leo’s experiences in WWI were similar to many Australian recruits enlisting in 1917, beginning with training camp in Australia and including trench warfare in Belgium and a familiarity with the medical corp.

No familial ties to the armed forces existed prior to Leo’s enlistment, and there was no ongoing involvement when either war ended. Although no record of Leo’s reasons for enlisting exists, it likely resulted from two complimentary motivators. A steady income that his work as a labourer did not always give him, and patriotic duty.[1]

It is probable Leo did not enlist when war was initially declared, as he and his wife were expecting their second child.[2] Their first passed away in 1914 at 6 weeks of age.[3] On 22 January 1917 at Melbourne Town Hall, amidst a struggling recruitment campaign, Leo enlisted at 22 years of age.[4]

One week after enlistment, Leo entered Royal Park camp in Victoria, where he was assigned to the 15th Machine Gun Company.[5] Five months later Leo would leave Australia on board the HMAT Suevic with over 1500 reinforcements.[6] Although the Suevic had three ports of call on its way to England, officers were the only soldiers allowed to disembark.[7] Inventive means of entertainment had to be employed for the 67 days troops spent on board.[8] These included boxing matches, ship-board versions of football, and more relaxed games such as egg and spoon races and quoits.[9] And what voyage would be complete without a crossing the line ceremony, complete with King Neptune, when the Suevic crossed into the Northern Hemisphere.[10] Training continued for the arriving reinforcements once they landed in England, with a further 14 weeks in a military depot at Salisbury Plain.[11] Here they were trained in specificities including trench routines, grenade throwing and instructions on how to deal with gas attacks.[12] During this time, Leo was transferred from the 15th Machine Gun Company to the 59th Battalion.[13] On 8 December 1917, Leo, along with the other 59th Battalion reinforcements, left England to march out to the front lines.[14]

The reinforcements for the 59th Battalion met up with the central unit in Belgium at Lindenhoek camp.[15] Here they were greeted with hot cocoa, a hot meal and a few hours of sleep before they rolled up their blankets, boarded a train and with snow falling, left the front line and headed to Enquin-sur-Baillons in France.[16] Leo’s arrival had coincided with the battalions reserve time, after weeks spent at the front. I would imagine it was a confusing period for Leo, marching into Belgium to the sound of artillery and enemy planes overhead, only to leave the area, without joining the fray, to do more training and drills and partake of a Christmas feast of roast turkey and plum pudding.[17]

The reprieve could not last, though, and after some time spent in reserve, the 59th Battalion would return to the front line at Messines Ridge in Belgium.[18] Here, heavy artillery and machine gun fire provided a soundtrack to the soldiers’ lives, and Leo would fully experience the noise of war for the first time.[19] The 59th Battalion continued to oscillate between reserve and front line fighters, however, while the battalion was fighting at Villers-Bretonneux in April 1918, Leo was at a base depot in Écault recovering from influenza, and would not rejoin his unit until July 1918.[20] Although, the Spanish Influenza had reached France in April 1918, it’s not clear from the records if Leo had Spanish Influenza or a more general influenza.[21]

On 8 August 1918, in the early hours of the morning, the 59th Battalion was a part of the force taking part in the Battle of Amiens.[22] Here, the battalion succeeded in their objective to advance to the town of Harbonnieres, where they placed a miniature Australian flag atop the church tower at the behest of the administrative commander of the AIF, General Birdwood.[23] With a well-fought victory and the flying Australian flag, one can imagine the sense of pride and patriotism that the soldiers of the 59th Battalion may have felt in this moment. However, one month later, after a period of heavy fighting near Perrone, changing orders that resulted in a long, unnecessary march and a night’s sleep in an open trench, Leo absented himself without leave for 4 days.[24] Whether Leo did this because of exhaustion or anger has not been passed down in family lore. Whatever Leo’s reasons, he surrendered himself and was censured with the loss of 13 days pay.[25] Given that Leo had elected to give 3/5 of his pay to his family in Australia, I am sure this loss in pay was also felt by them.[26]

Just 3 days before the 59th Battalion would withdraw from the front for what would be its final rest, Leo was gassed.[27] He was taken to a clearing station via field ambulance, from where he was transferred to a nearby general hospital where he would remain for a month, before marching back out to his unit.[28]

Armistice was declared on 11November 1918. Leo stayed in the field, but at rest, with his unit until he was granted leave to the United Kingdom (UK) in January 1919.[29] Although there’s no personal communications to outline what celebrations Leo partook in while in the UK, his admittance to hospital with gonorrhoea a week after he returned from leave, does indicate what at least part of his celebrations involved.[30]

Leo spent the remainder of his time overseas receiving treatment for gonorrhoea.[31] Over 48,000 Australian soldiers in WWI underwent treatment for gonorrhoea, which was a painful process in the early 1900s, involving twice daily procedures for an average of 7 weeks.[32] Leo’s delay in returning home once peace was declared was due to a variety of factors. These included a lack of suitable ships, a priority repatriation system, as well quarantine procedures Australia had in place due to the Spanish Influenza.[33]

Many returning veterans had physical and/or psychological scars that had a devastating impact on their attempts to return to civilian life.[34] Leo’s return to Australia had a rocky start. He was granted property at Kamarooka Street, Sunshine under The War Service Homes Act 1918-1923, but fell into arrears on payments.[35] He then spent time apparently dodging government officials and moving from house to house and job to job. Eventually, he was found living in Fairfield and working at the Australian Paper and Pulp Co., Ltd under the alias, J. Short.[36] A heavy drinker before the war, these habits continued on his return.[37] However, once he’d been found by government officials and agreed to pay back money owed, Leo maintained steady employment as a labourer and later a driver.[38] Leo and his wife continued to have children, with another son born almost one year to the day after his return.[39] Leo expressed pride in his contribution to the war effort, but the only family story that remains from his service was his desire to re-enlist in WWII and his sadness when, due to health, he was not able to actively serve.[40]

No one’s war experience would be the same. However, aspects of Leo’s experiences would have been familiar to many veterans. The continual training, trench warfare, the constant noise and the loss of comrades and mates. Leo’s ability to meaningfully re-engage with his family and the civilian workforce was not achievable for many, although, I’m sure, hoped for by most.

[1] Bill Gammage, The Broken Years: Australian Soldiers in the Great War, Australian National University Press, Canberra, 1974; Australian Government: Department of Veterans’ Affairs, ‘Training Australian army recruits during World War I’, Anzac Portal website, n.d., https://anzacportal.dva.gov.au/wars-and-missions/ww1/military-organisation/training#2, accessed 10 September 2024; Service record of Percival Victor Leopold Short, Australian Imperial Force Personnel Dossier, 1939-1948, National Archives of Australia, B883, VX30269, p 24.

[2] Birth Registration of Walter George Percival Short, born 21 July 1915, Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, Victoria, 24203/1915.

[3] Death Registration of Philas Olive Irene Short, died 31 March 1914, Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, Victoria, 6954/1914.

[4] Service record of Percival Victor Leopold Short, p 24; Gammage, The Broken Years; Australian Soldiers in the Great War; ‘The Call to Arms’, Age, 6 Jan 1917, p 11, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/155198035?searchTerm=town%20hall%20enlistment, accessed 8 September 2024; ‘Enlistments in Melbourne’, Age, 23 Jan 1917, p5, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/155189082?searchTerm=town%20hall%20enlistment, accessed 8 September 2024; ‘Enlistments Still Poor’, Age, 13 January 1917, p 11, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/155187707?searchTerm=town%20hall%20enlistment, accessed 8 September 2024.

[5] Service record of Percival Victor Leopold Short, Australian Imperial Force Personnel Dossier, 1939-1948, National Archives of Australia, B883, VX30269, p 27.

[6] Troopship records for H.M.A.T. Suevic, Troopship records, 1914-1918 War Suevic: Melbourne June 1917 – Liverpool August 1917, Australian War Memorial, AWM7, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C2840849?image=2, accessed 10 September 2024.

[7] Troopship records for H.M.A.T. Suevic.

[8] Troopship records for H.M.A.T. Suevic.

[9] Troopship records for H.M.A.T. Suevic; Souvenir of The Heavic: troop newspaper of H.M.A.T. “Suevic” (A29) [At sea]: H.M.A.T. “Suevic” 1917-1917, State Library of Victoria, accessed 27 August 2024.

[10] Souvenir of The Heavic: troop newspaper of H.M.A.T. “Suevic”.

[11] Australian Government: Department of Veterans’ Affairs, ‘Training Australian army recruits during World War I’; Service record of Percival Victor Leopold Short, Australian Imperial Force Personnel Dossier, 1939-1948, National Archives of Australia, B883, VX30269, p 5.

[12] Australian Government: Department of Veterans’ Affairs, ‘Training Australian army recruits during World War I’; Memorandum concerning the establishment of a training centre at Salisbury Plain for the AIF, June 1916, Australian War Memorial, AWM27 302/40, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C2746084, accessed 10 September 2024.

[13] Service record of Percival Victor Leopold Short, p 5.

[14] Service record of Percival Victor Leopold Short, p 5; Diary entry for 14 December 1917, Australian Imperial Force unit war diary, 59th Infantry Battalion, Australian War Memorial, AWM4 23/76, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1339120, accessed 9 September 2024.

[15] Diary entry for 14 December 1917, AIF unit war diary, 59th Infantry Battalion.

[16] Diary entry for 14 December 1917, AIF unit war diary, 59th Infantry Battalion; Diary entry for 15 December 1917, Australian Imperial Force unit war diary, 59th Infantry Battalion, Australian War Memorial, AWM 23/76, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1339120, accessed 11 September 2024, Diary entry for 16 December 1917, Australian Imperial Force unit war diary, 59th Infantry Battalion, Australian War Memorial, AWM 23/76, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1339120, accessed 11 September 2024.

[17] Diary entry for 25 December 1917, Australian Imperial Force unit war diary, 59th Infantry Battalion, Australian War Memorial, AWM 23/76, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1339120, accessed 11 September 2024; History of the 59th Btn. 1st A.I.F., Belgrave: 59th Battalion A.I.F. Association, 1968, pp 15-34, https://find.slv.vic.gov.au/permalink/61SLV_INST/1sev8ar/alma9922617903607636, accessed 25 August 2024.

[18] History of the 59th Btn. 1st A.I.F., pp 15-34; Diary entry for 11 March 1918, Australian Imperial Force unit war diary, 59th Infantry Battalion, Australian War Memorial, AWM 23/76, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1339120, accessed 11 September 2024.

[19] Diary entry for 11 March 1918, AIF unit war diary, 59th Infantry Battalion.

[20] Service record of Percival Victor Leopold Short, Australian Imperial Force Personnel Dossier, 1939-1948, National Archives of Australia, B883, VX30269, p 6; Service record of Percival Victor Leopold Short, Australian Imperial Force Personnel Dossier, 1939-1948, National Archives of Australia, B883, VX30269, p 9; Australian War Memorial, ‘59th Australian Infantry Battalion’, Australian War Memorial website, n.d., https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/U51499, accessed 20 August 2024.

[21] Mariano Martini, Valentina Gazzaniga, Nicola Luigi Bragazzi and Ilaria Barberis, ‘The Spanish Influenza Pandemic: A Lesson from history 100 years after 1918’, Journal of Preventive Medicine and Hygiene, 2019, 60(1), http://doi.org/10.15167/2421-4248/jpmh2019.60.1.1205, accessed 14 September 2024.

[22] Diary entry for 8 August 1918, Australian Imperial Force unit war diary, 59th Infantry Battalion, Australian War Memorial, AWM 23/76, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1339120, accessed 11 September 2024.

[23] Diary entry for 8 August 1918, Australian Imperial Force unit war diary, 59th Infantry Battalion.

[24] Diary entry for 4 September 1918, Australian Imperial Force unit war diary, 59th Infantry Battalion, Australian War Memorial, AWM 23/76, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1339120, accessed 11 September 2024; Service record of Percival Victor Leopold Short, p 9.

[25] Service record of Percival Victor Leopold Short, p 9.

[26] Service record of Percival Victor Leopold Short, p 24.

[27] Service record of Percival Victor Leopold Short, p 9.

[28] Service record of Percival Victor Leopold Short, p 9; Australian War Memorial, ‘59th Australian Infantry Battalion’; Service record of Percival Victor Leopold Short, Australian Imperial Force, 1939-1948, National Archives of Australia, B883, VX30269, p 10.

[29] Service record of Percival Victor Leopold Short, Australian Imperial Force, p 10.

[30] Service record of Percival Victor Leopold Short, Australian Imperial Force, p 10.

[31] Service record of Percival Victor Leopold Short, Australian Imperial Force, 1939-1948, National Archives of Australia, B883, VX30269, p 7; Service record of Percival Victor Leopold Short, Australian Imperial Force, p 10.

[32]Ian Howie-Willis, ‘The Australian Army’s Two ‘Traditional’ Diseases: Gonorrhea and Syphilis – A Military-Medical History During the Twentieth Century’, History, 2023, vol 27 (1), https://doi-ds.org/doilink/03.2023-19781933/JMVH Vol 27 No 1.

[33] Australian Government: Department of Veterans’ Affairs, ‘Repatriation of Australians in World War I’, Anzac Portal website, n.d., https://anzacportal.dva.gov.au/wars-and-missions/ww1/politics/repatriation#:~:text=The%20process%20by%20which%20Australian,Government%20Department%20of%20Veterans’%20Affairs, accessed 10 September 2024; National Museum Australia, ‘Influenza Pandemic’, National Museum Australia website, n.d., https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/influenza-pandemic, accessed 12 September 2024.

[34] Peter Hart, ‘Armistice 1918’, Wartime, vol. 44, 2008, pp.46-49, https://www.awm.gov.au/wartime/44/page47_hart, accessed 10 September 2024.

[35] Miscellaneous papers for Percival Victor Leopold Short, 1923-1924, B741, National Archives of Australia, https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/DetailsReports/ItemDetail.aspx?Barcode=396954&isAv=N, accessed 16 October 2024.

[36] Miscellaneous papers for Percival Victor Leopold Short, 1923-1924, B741, National Archives of Australia, accessed 16 October 2024.

[37] Martin Frank Horan, conversation with Vera May Martin [transcription], Parkdale, Victoria, 20 December 1982, original held by author; ‘Driving under the influence’, 24 March 1936, p 5, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/205263127?searchTerm=%22Leopold%20Short%22, accessed 26 August 2024.

[38] Electoral roll entry for Percival Victor Leopold Short, Alphington, Bourke, Victoria, 1919, in Australia, Electoral Rolls, 1903-1980, Ancestry.com, accessed 8 September 2024; Electoral roll entry for Percival Victor Leopold Short, Carlton, Bourke, Victoria, 1928, in Australia, Electoral Rolls, 1903-1980, Ancestry.com, accessed 8 September 2024; Electoral roll entry for Percival Victor Leopold Short, Alphington, Batman, Victoria, 1936, in Australia, Electoral Rolls, 1903-1980, Ancestry.com, accessed 8 September 2024.

[39] Birth Registration of William Henry Short, born 21 June 1920, Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, Victoria, 10946/1920.

[40] Service record of Percival Victor Leopold Short, Australian Imperial Force, 1939-1948, National Archives of Australia, B883, VX30269, p 16.